My mother was a fantastic baker and cook. She could take nothing and make something wonderful from it. Unfortunately, I didn't appreciate it when I was growing up. They practically had to force feed me like those poor geese for foie gras. But what I did love, was anything my mother baked and is why, in hindsight, I went into the baking business.

My mother was a fantastic baker and cook. She could take nothing and make something wonderful from it. Unfortunately, I didn't appreciate it when I was growing up. They practically had to force feed me like those poor geese for foie gras. But what I did love, was anything my mother baked and is why, in hindsight, I went into the baking business.

My mother and grandparents were immigrants from what was then, Yugoslavia. Just as in this country, different parts of the country had different assets. Mother lived in an area rich in dairy with butter, eggs and cream at their disposal. I would watch my mother and grandmother on Sunday's, spread a clean, white tablecloth over a large, round table over which freshly made phyllo would be stretched. I could scarcely understand a word as they chatted away in Serbian.

My job was to sweep up the scraps after the thick edges were removed and some of the paper thin dough fell to the floor. While most people can't imagine a dough being stretched so thinly a newspaper could be read through it, I thought everybody made it. After it had been stretched to transparency, a spoon would be dipped into melted butter and I can still see my mother and grandmother holding it high and waving it over and over the transparent dough as the golden drops of liquid fell from the spoon dotting the surface. It would then be folded upon itself and more butter would be drizzled.

Eventually, layers and layers and layers of phyllo would be stacked upon itself, then filled with apples, cheese, cherries or whatever was at hand. Sugar and spices would be rained down upon the filling and then the dough would be folded over itself enfolding the filling and the strudels would be placed on baking pans, brushed with more butter (no one had heard of cholesterol) and baked to a golden turn. There are no words to describe the experience of crispy golden, flaky layers of tissue thin dough fresh out of the oven with a warm, juicy filling just waiting for the first bite. I had no idea how special this was nor how lucky I was.

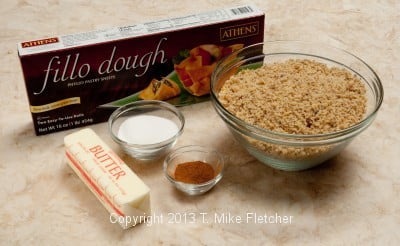

One of my mothers recipes that was always a favorite was baklava. Layers of flaky phyllo filled with nuts, spices and sugar then, after baking, basted liberally with a honey syrup that is allowed to soak in. The surprise is the phyllo stays crisp if one rule is followed. The temperature of the syrup and baked baklava is the key. If the baklava is hot, the syrup must be cold when it is poured on. If the baklava is cold, the syrup must be hot. There are many variations on this recipe with most of them featuring rosewater as its flavoring. This one differs in that the flavoring is dark rum. To keep the syrup clear and golden, the spices which flavor it are kept whole. Cinnamon sticks and whole cloves as well as strips of lemon rind are used to infuse the honey sugar syrup with flavor.

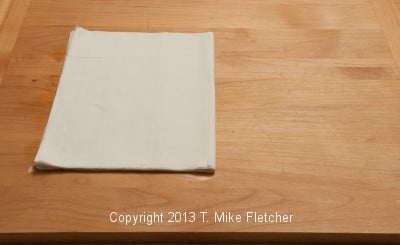

Phyllo is the traditional spelling of this pastry but it has been anglicized to fill but the pronunciation remains fee-low. The word in Greek means "leaf". Commercially made of flour, water, salt and oil, the dough is mixed and allowed to rest so the gluten in the flour relaxes. After a suitable rest, the dough is rolled and stretched very thin, and then cut into individual leaves. Cornstarch is often sprinkled between the leaves to keep them from sticking together. The phyllo is sealed in plastic to prevent drying and maintain freshness. Stored in the refrigerator, it will last a month, or in the freezer it will keep indefinitely. It is offered by various companies in various thicknesses. The very thin has 20 to 24 leaves per pound and the thicker phyllo has about 14 leaves per pound. I use only the thinnest phyllo as it is both more readily available and yields a more delicate, flaky product.

Good phyllo will have smooth edges, not crumbly or dry, and the leaves will separate one from the other easily. If too much moisture reaches it, the dough will become sticky or gummy, a condition most likely found when it has been frozen and allowed to thaw improperly. But too little moisture results in a dry dough with cracked edges. This can usually be remedied by placing the phyllo on a baking sheet and covering it with a clean, dry kitchen towel. Wet another towel, squeeze most of the water out and place it over the dry one. Finally cover the entire assembly with another dry towel. Allow to sit for 30 to 60 minutes, depending upon the original condition of the dough. Check the progress frequently, as too much moisture is no better than not enough. When the top leaves have absorbed as much moisture as they need, turn the dough over so the bottom can be rejuvenated.

If the phyllo is frozen, it needs to be defrosted in such a way as to reduce or eliminate the condensation that forms inside the sealed plastic bag, as this is what causes the dough to become sticky. Allow it to deforest in the refrigerator for 24 to 36 hours. Do not defrost at room temperature.

It is important the butter be very liquid but no more than lukewarm. If the butter cools and thickens, rewarm it. It is not necessary to soak the leaves in butter; in fact, that is counterproductive, as the leaves will lose their individuality and much of the butter will also leak out during baking. A light brushing with butter is all that is needed. The "book method" of buttering phyllo is the most convenient. With the dough folded in the middle, it can be buttered quickly half a leaf at a time.

When cutting unbaked phyllo, it is preferable to use a sharp knife and an up-and-down sawing motion.

Phyllo should always be baked to a deep golden brown to ensure that it is cooked throughout. Underbaked, it will be soggy or limp. However, over baking causes the dough to become tough.

Unused portions of phyllo dough, as long as they have not been buttered or otherwise prepared, may be rewrapped and frozen. If used within 10 to 14 days it may be refrigerated.

The above is from "The New Pastry Cook", my first cookbook, published by William Morrow & Co., 1986.

When I wrote the passage from my book, cooking sprays had not been invented. I urge you not to use them now. I know it is quicker but not better. If you are going to make this classic Greek pastry, I urge you to use butter. You don't need to drown the leaves in butter, in fact that is contradictory. Brush very lightly and the entire leaf does not have to be covered. Eating a piece won't hurt you, just don't eat the whole thing - as can my son!

Today this recipe is made easy with the use of phyllo that can be found in the frozen section of grocery stores. If this is the first time you will be making this age old treasure, it is easily done in steps as the syrup must be made the day or days before. If the syrup is to be held longer, remove the spices and lemon rind and leave at room temperature until needed.

The book method of buttering the layers makes this almost foolproof and much quicker than the old way of buttering one sheet at a time and placing another on top. It is important to prepare the layers quickly so they don't dry out. Working with phyllo is really quite easy once you know this method. It can be used with sweet or savory fillings, lends itself to a variety of shapes and can generally be filled and frozen to be baked off at a different time.

We will explore more recipes with phyllo as this blog goes along.

Honey Syrup

1 cup sugar (200 grams or 7 ounces)

Rind of ½ lemon, peeled in long strips

5 whole cloves

3 cinnamon sticks

½ cup honey

2 tablespoons lemon juice

1 ½ tablespoons dark rum

One or two days before using, combine the water, sugar, lemon rind, cloves and cinnamon sticks in a saucepan.

Baklava

1 ½ teaspoons cinnamon

¾ pound walnuts, finely chopped (340 grams or 12 ounces)

½ cup butter (114 grams or 4 ounces)

½ pound phyllo

1 recipe honey syrup, above

Preheat oven to 325 degrees. Spray a 9x9x2 inch square baking dish. Set aside.

Combine the sugar and cinnamon

mixing well.

If the walnuts are not finely chopped, place in a processor and pulse to cut finely but do not turn them to powder. Divide into 3 bowls of 114 grams or 4 ounces each.

The package of phyllo used here comes in 2 sealed packages.

Using 5 sheets of phyllo, repeat the buttering in the same manner. Use another ⅓ of the nut mixture. Repeat with 5 more sheets of phyllo and the last of the nut mixture. Fold and butter the last of the phyllo and place on top of the nuts.

Trim the phyllo to the top of the pan,

If there is any butter left, pour it over the phyllo. Bake for 1 hour, covering lightly towards the end to prevent it from over browning if necessary.

Remove from the oven and slowly pour ½ of the syrup over the hot pastry at once.

As you pour, you can hear the crisp leaves making an audible crackling noise as the cool syrup hits it. An hour later, pour the remaining syrup over the pastry.

This will keep well for days if it is covered.

vera parker says

Thanks for the photos explaining the "book" method. I, too, grew up watching Mom pull out the home made strudel dough. You brought back many memories for me.

hfletcher says

I think anyone fortunate enough to have seen this made or participated in the making of phyllo will never forget it.

Mari gold says

You are awesome! Your detail in writing a recipe are SOO precise ,reading this brought back memories of two friends, sister in laws that cooked and baked and they were marvelous ladies and bakers. They were Armenian and called this Paklava, they used a honey syrup slightly different , lots of butter that was rationed during the war, and made their own phylo. I have made it for many years but not lately. Thanks to you, I will do it soon and follow your recipe. I still have their pan, a large round one. You are a treasure and make my day, thank you,mari

hfletcher says

Thanks so much Mar - you make MY day.