Yeast is a primary ingredient in many breads. This white paper is a comprehensive discussion of the types of yeasts, it's uses, lean and rich doughs, preferments, temperatures, proofing and making a proofer, the structure of doughs, finishes, storage, how much to use, and more.

What is Yeast

Yeast cells are single cell living organisms that are a part of the fungi group. Approximately 15 million are in one pound of compressed yeast. One of the oldest living organisms, dating back to the Egyptians, it continues to help mankind make bread and beer. Hieroglyphs show Egyptians 5,000 years ago in bread bakeries and making beer - maybe not the beer we know, but beer nevertheless. Both of these were dependant upon yeast, just as they are today. But it was Louis Pasteur who proved that living yeast is necessary for fermentation.

The yeast most often used today is Saccharomyces cerevisiae which translates in Latin to “sweet fungi of beer.” There are 1,500 strains of yeast that have been identified but that is just 1% of the strains believed to exist but are not yet named.

The yeast we use for baking is a domesticated wild yeast that manufacturing has stabilized and made 200 times stronger than it was in the wild. Plant scientists decide which characteristics of wild yeast are desirable and put them on a diet of cornsyrup to make them reproduce. When they reproduce to the desired degree, they are filtered, dried, packaged and shipped off to market.

The ability of yeast to rise is affected by food, moisture, the right acid balance (pH) and a temperature between 70 and 100 degrees. However, for the best taste the dough should rise at the lowest temperature so it can develop flavor.

While the correct amount of sugar will enhance yeast development, too much of it will either slow it down or kill it off. Salt should never be mixed directly with yeast. Salt is necessary to slow down the development of the yeast.

Dough heavy in sugar or fat (think eggs, butter) is a very slow riser. To compensate for this a sponge is often used. These will be discussed later in the article. The optimum amount of sugar, without using a sponge, is no more than ¼ cup per 3 cups of flour. There are basically two types of yeast dough: Rich and lean. A rich dough is a sweet dough and is, as you can guess, one that is heavy in sugar and fat. A lean dough is low in sugar and fat. Each of these is treated differently when it comes to yeast.

Types of Yeast

Baker’s yeast, like baking powder and baking soda, is used to leaven baked goods. Baking powder and baking soda react chemically to produce the carbon dioxide that makes the baked goods rise. Yeast, however, does not cause a chemical reaction. Instead, the carbon dioxide it produces in the form of bubbles is the result of the yeast literally feeding on the dough causing the dough to rise until killed by heat.

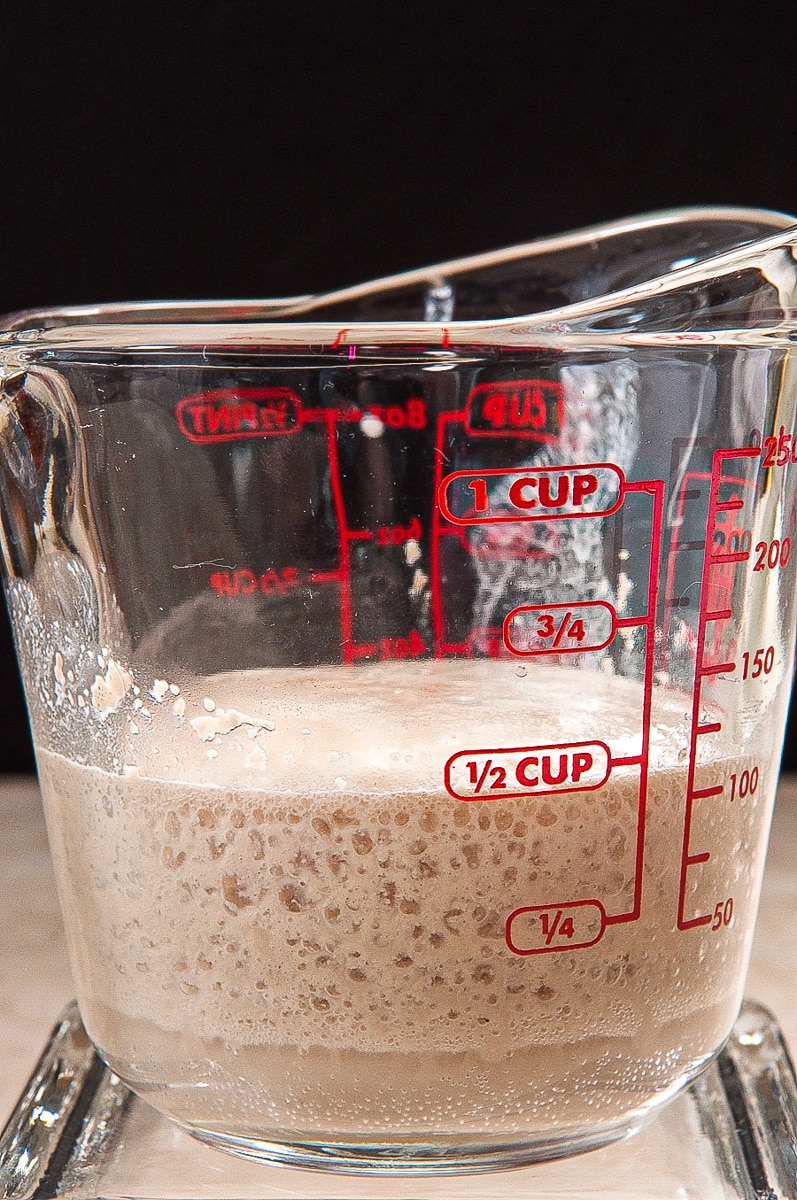

Today, there are a variety of yeasts offered but the two most important used by home bakers are instant or active dry yeast. All the others are variations of these two. While it was necessary in the past to dissolve active dry yeast in water, it can now be added directly to the dry ingredients as instant yeast is. If you are unsure your active dry yeast is still active, dissolve it in a ¼ cup warm water with ½ teaspoon sugar. In about 10 minutes or so it should bubble up to the ½ cup measure.

Active Dry Yeast

According to King Arthur Flour, Active Dry Yeast is considered slower to get going but eventually catches up to the instant yeast which is a quicker starting yeast. Fleischmann’s and Red Star are the two most prevalent active dry yeasts in the super markets. They come in 3 packets and in jars as well as vacuum packed.

Because active dry yeast is subjected to extremely high temperatures to dry out cake yeast and form the granules, many of its cells are destroyed in the process.

Because the outer cells are dead, this yeast must be dissolved in a warm liquid to activate the living cells in the center.

Instant Yeast

Instant Yeasts referred to as Instant, Rapid Rise, Bread or Pizza yeast are processed to 95% dry matter but are dried more gently resulting in every dried particle is living and active. The yeast can be added directly to the dry ingredients without first proofing it in water. However, if both salt and yeast are added to the same bowl as the flour, they should be put on opposite sides of the bowl until mixed as salt in direct contact will kill the yeast.

SAF instant yeast is the leader among instant yeasts although Fleishman’s is on many grocer’s shelves. SAF is produced in France by the LeSaffre company who is the largest producer of yeasts in the world. Red Star also has a large share.

Although today’s active dry yeast and instant yeast can be used interchangeably, it is a common practice to use about ¼ less instant yeast than active dry yeast by artisan bread bakers. It is also not recommended to use the same amount of instant yeast as active dry in a bread machine as the machines use a higher temperature to raise the dough. If using instant yeast in a bread machine reduce it by about 25% to avoid the dough over-rising and then collapsing.

General Guide to Purchasing Yeast

Thanks to www.asweetpeachef.com for this.

“Granted, purchasing yeast can be a confusing process due to different manufacturers not using the same names for their products or using the same names for different types of yeast. That being said, here’s a general guide to purchasing yeast using popular labeling and product instructions:

- Cake (Moist) – traditional live yeast; needs to be dissolved in water

- Active Dry – traditional dry yeast; needs to be dissolved usually with sugar

- Instant – contains small amount of yeast enhancer; does not need to be dissolved

- Bread Machine – exactly the same as Instant but in a different package

- Rapid-Rise – larger amount of yeast enhancers and other packaging changes to the granules; does not have to be dissolved”

How Much Yeast to Use

This chart from Red Star Yeast.

It includes cake yeast which is rarely found but I left it in as a comparison.

To use instant yeast in place of active dry yeast, 1 ¾ teaspoon of instant yeast is used in place of 2 ¼ teaspoons of active dry yeast.

| Flour | Dry Yeast | Cake Yeast | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cups* | packages (¼ oz) | grams | teaspoons | ounces** |

| 0-4 | 1 | 7 | 2+¼ | ⅔ (⅓ of a 2oz. cake) |

|

4-8 |

2 |

14 |

4+½ |

1+⅓ |

|

8-12 |

3 | 21 |

6+¾ |

2 |

|

12-16 |

4 |

28 |

9 |

2+⅔ |

|

16-20 |

5 |

35 |

11+¼ |

3+⅓ |

However, the amount of yeast to use can be altered by whether the recipe is a a lean or rich dough. Rich doughs that include sugar, eggs and butter require more yeast than lean doughs consisting of water, flour, salt, and yeast.

According to Red Star, if the ratio of sugar to flour is more than ½ cup sugar to 4 cups flour, an additional 2 ¼ teaspoons of yeast per recipe is needed.

If too much yeast is used, the bread can rise too quickly, resulting in not much flavor and it can become misshapen when baked.

Storage

Depending upon how often you use yeast, it can be stored in the refrigerator or in the freezer for longer storage. Packages of active dry yeast contain 2 ¼ teaspoons per pack.

Instant yeast comes in a jar or, in larger amounts, in vacuum packages. I usually buy the larger package and transfer the yeast to an airtight container and store it in the freezer.

A smaller container is kept in the refrigerator for everyday use and refilled from the freezer as necessary.

Working with Yeast Dough

Because so many different factors go into yeast dough rising, it is difficult to give definite times. If the room is cold, it will take longer, if it is too warm, it will go faster.

Also making a big difference the amount of yeast used. Artisan breads generally use smaller amounts of yeast for longer rising dough so it develop more flavor. American types of loaf breads are prone to using more yeast for a quicker rise, especially if ingredients other than flour, water, salt and yeast are used.

Sweet doughs invariably use more yeast per cup of flour.

There is a temptation by some bread bakers to use more yeast for a quicker rise. The problem with that is it produces CO2, alcohol and organic acids at a much faster rate. Acid, such as the alcohol produced, weakens the gluten in the dough causing it not to rise well. In other words, too much yeast will cause the opposite of a quick rising dough.

You can always cut back on the yeast, which will cause the dough to rise slower creating a very strong gluten structure to support a good rise in the oven. Allowing dough to rise overnight with a small amount of yeast will product a superior loaf.

One of the things that can greatly alter the rising time is how frequently you make bread. If you bake a lot of yeast products, there will be wild yeast in your kitchen which will aid in the rising of your products. If you bake infrequently with yeast, very little will be in your kitchen so it may take longer for your dough to rise.

While King Arthur gives some guidelines for how much yeast to use, if you are a beginner, I suggest following a dependable recipe. A basic dough using only flour, water, salt and possibly a bit of oil or sugar is fine to leave out on the counter for an all day countertop rise. These include baguettes, focaccia, and pizza doughs.

Any product that uses dairy should be refrigerated for a slow rise. I usually make my sweet dough the day before I want to shape and bake it as it is easier to handle that way. The dough won’t be as springy when rolling and will shape much easier. I allow it a first rise at room temperature, punch it down and then transfer it to the refrigerator.

Dough Structure

The structure of the dough can be affected by many things. If it is a lean dough, the amount of water in the dough will give it a tight structure or an open, holey one. Baguettes have a tighter finished structure using less water than does ciabatta, which can be so wet as to be difficult to manage for the best open structure when baked. It’s sort of like trying to manage a wiggly blob when shaping.

Sweet dough will always have a tighter structure due to the ingredients, including the liquid.

Also the liquid used in the dough will make a difference. Yeast loves potato water and literally gobbles it up.

In the past, the instructions for loaf breads at the time were to keep adding flour while kneading the dough until it no longer stuck to the board. It invariably ended up with too much flour in it. The lack of hydration is what made the dough stale so quickly. Later I discovered that the dough, lean or sweet, should be soft which does not necessarily equate to sticky although it sometimes does.

While some people take great pride in hand kneading their bread to perfection, I am not one of them. I simply don’t have the time nor the desire. So I use my heavy duty mixer and a dough hook to knead my dough. I do knead it by hand for a minute or so to smooth it out before putting them to rise.

In any case, the kneaded dough should pass the windowpane test. A small piece of dough is stretched thinly with your fingers until you can see through it. If it breaks or will not stretch thinly enough, knead it some more until it does.

The Flavor in Bread

The flavor of bread can be controlled by three things. The flour used, the amount of browning during baking and the flavor built up during fermentation.

Pre-ferments

There are several reasons for wanting to increase the amount of organisms in your dough without adding additional yeast. Among them are rich doughs. A lot of sugar, eggs, milk or cream will slow the ability of the dough to rise. However, loading up these doughs with lots of yeast can lead to a “ yeasty taste” and can actually be counterproductive. So a sponge is often used to introduce more living yeast cells into the dough without increasing the amount of yeast.

A sponge consists of a small amount of flour, some yeast, water and sometimes a pinch of sugar are mixed together. They are then covered and allowed to rise until doubled. Since yeast is a living organism, you can see how when the sponge has risen, you have just increased enormously the number of live organisms ready to help raise a rich dough.

Lean dough often depend upon variations of this theme under the names, bigas (Italian), levains (French) Poolish, a liquid starter or sometimes they are just called starters. They all do the same thing, which is to allow very little yeast to be used. These often ferment for several hours or overnight introducing more flavor into the dough.

Another pre-ferment is to save a piece of dough from a batch made the day before and add it to the new batch of dough.

King Arthur Flours has a wonderful discussion on preferments that help clarify the confusing differences among all the different types. It is so important, I have included the entire discussion here.

“A preferment is a preparation of a portion of a bread dough that is made several hours or more in advance of mixing the final dough. The subject of preferments is one that can cause immense confusion among bakers. The variety of terminology can bewilder even the most experienced among us. Words from foreign languages add their contribution to the complexity.

A preferment is a preparation of a portion of a bread dough that is made several hours or more in advance of mixing the final dough. The preferment can be of a stiff texture, it can be quite loose in texture, or it can simply be a piece of mixed bread dough. Some preferments contain salt, others do not. Some are generated with commercial yeast, some with naturally occurring wild yeasts. After discussing the specific attributes of a number of common preferments, we will list the benefits gained from their use.

- chef

- pâte fermentée

- levain

- sponge

- madre bianca

- mother

- biga

- poolish

- sourdough

- starter

These terms all pertain to preferments; some are quite specific, some broad and general. The important thing to remember is that, just as daffodils, roses, and tulips all are specific plants that fall beneath the heading of “flowers,” in a similar way the above terms all are in the category of “preferments.” Let’s examine several of the terms listed in more detail.

Pâte fermentée, biga, and poolish, are the most common preferments which use commercial yeast. As such, we can place them loosely in a category of their own. We place sourdough and levain in a separate category.

pâte fermentée

Pâte fermentée is a French term that means fermented dough, or as it is occasionally called, simply old dough. If one were to mix a batch of French bread, and once mixed a portion were removed, and added in to a new batch of dough being mixed the next day, the portion that was removed would be the pâte fermentée. Over the course of several hours or overnight, the removed piece would ferment and ripen, and would bring certain desired qualities to the next day's dough. Being that pâte fermentée is a piece of mixed dough, we note that it therefore contains all the ingredients of finished dough, that is, flour, water, salt, and yeast.

biga

Biga is an Italian term that generically means preferment. It can be quite stiff in texture, or it can be of loose consistency (100% hydration). It is made with flour, water, and a small amount of yeast (the yeast can be as little as 0.1% of the biga flour weight). Once mixed, it is left to ripen for at least several hours, and for as much as 12 to 16 hours. Note that there is no salt in the biga. Unlike pâte fermentée, which is simply a piece of mixed white dough which is removed from a full batch of dough, the biga, lacking salt, is made as a separate step in production.

poolish

Poolish is a preferment with Polish origins. It initially was used in pastry production. As its use spread throughout Europe it became common in bread. Today it is used worldwide, from South America to England, from Japan to the United States. It is by definition made with equal weights of flour and water (that is, it is 100% hydration), and a small portion of yeast. Note again the absence of salt. It is appropriate here to discuss the quantity of yeast used. The intention is not to be vague, but it must be kept in mind that the baker will manipulate the quantity of yeast in his or her preferment to suit required production needs.

For example, in a bakery with two or three shifts, it might be suitable to make a poolish or any other preferment and allow only 8 hours of ripening. In such a case, a slightly higher percentage of yeast would be indicated in the preferment. On the other hand, in a one-shift shop, the preferment might have 14 to 16 hours of maturing before the mixing of the final dough. In this case the baker would decrease the quantity of yeast used. Similarly, ambient temperature must be considered. A preferment that is ripening in a 65°F room would require more yeast than one in a 75°F room.

sourdough and levain

The words sourdough and levain tend to have the same meaning in the United States, and are often used interchangeably. This however is not the case in Europe. In Germany, the word sourdough (sauerteig) always refers to a culture of rye flour and water. In France, on the other hand, the word “levain” refers to a culture that is entirely or almost entirely made of white flour. While outwardly these two methods are different, there are a number of similarities between sourdough and levain. Most important is that each is a culture of naturally occurring yeasts and bacteria that have the capacity to both leaven and flavor bread. A German-style culture is made using all rye flour and water.

A levain culture may begin with a high percentage of rye flour, or with all white flour. In any case, it eventually is maintained with all or almost all white flour. While a rye culture is always of comparatively stiff texture, a levain culture can be of either loose or stiff texture (a range of 50% hydration to 125% hydration). With either method, the principle is the same. The baker mixes a small paste or dough of flour and water, freshens it with new food and water on a consistent schedule, and develops a colony of microörganisms that ferment and multiply. In order to retain the purity of the culture, a small portion of ripe starter is taken off before the mixing of the final dough. This portion is held back, uncontaminated by yeast, salt, or other additions to the final dough, and used to begin the next batch of bread.

One important way in which a sourdough and levain are different from pâte fermentée, biga, and poolish, is that the sourdough and levain can be perpetuated for months, years, decades, and even centuries. When we make a preferment using commercial yeast, it is baked off the next day. We then begin the process again, making a new batch of preferment for the next day’s use. It would be tempting to say the pâte fermentée can be perpetuated, since each day we simply take off a portion of finished dough to use the following day. This is not actually the case. We could not, for example, go on vacation for a week and come back to a healthy pâte fermentée, whereas we could leave our sourdough or levain culture for a week or more, with a minimum of consequences.

During the initial stages in the development of a sourdough or levain culture, it is common to see the addition of grapes, potato water, grated onions, and so on. While these can provide an extra nutritional boost, they are not required for success. The flour should supply the needed nutrients for the growing colony. Keep in mind, however, that when using white flours, unbleached and unbromated flour, such as those produced by King Arthur® Flour, are the appropriate choice. Vital nutrients are lost during the bleaching process, making bleached flour unsuitable.

How does the baker know when his or her preferment has matured sufficiently and is ready to use? There are a number of signs that can guide us. Most important, it should show signs of having risen. If the preferment is dense and seems not to have moved, in all likelihood it has not ripened sufficiently. Poor temperature control, insufficient time allowed for proper maturing, or a starter that has lost its viability can all account for the problem.

When the preferment has ripened sufficiently, it should be fully risen and just beginning to recede in the center. This is the best sign that correct development has been attained. It is somewhat harder to detect this quality in a loose preferment such as a poolish. In this case, ripeness is indicated when the surface of the poolish is covered with small fermentation bubbles. Often CO2 bubbles are seen breaking through the surface.

There should be a pleasing aroma that has a perceptible tang to it. Take a small taste. If the preferment has ripened properly, we should taste a slight tang, sometimes with a subtle sweetness present as well. The baker should keep in mind that a sluggish and undeveloped preferment, or one that has gone beyond ripeness, will yield bread that lacks luster, and suffers a deficiency in volume and flavor.

There are a number of important benefits to the correct use of preferments, and they all result from the gradual, slow fermentation that is occurring during the maturing of the preferment:

- Dough structure is strengthened. A characteristic of all preferments is the development of acidity as a result of fermentation activity, and this acidity has a strengthening effect on the gluten structure.

- Superior flavor. Breads made with preferments often possess a subtle wheaty aroma, delicate flavor, a pleasing aromatic tang, and a long finish. Organic acids and esters are a natural product of preferments, and they contribute to superior bread flavor.

- Keeping quality improves. There is a relationship between acidity in bread and keeping quality. Up to a point, the lower the pH of a bread, that is, the higher the acidity, the better the keeping quality of the bread. Historically, Europeans, particularly those in rural areas, baked once every two, three, or even four weeks. The only breads that could keep that long were breads with high acidity, that is, levain or sourdough breads.

- Overall production time is reduced. Above all, to attain the best bread we must give sufficient time for its development. Bread that is mixed and two or three hours later is baked will always lack character when compared with bread that contains a well-developed preferment. By taking five or ten minutes today to scale and mix a sourdough or poolish, we significantly reduce the length of the bulk fermentation time required tomorrow. The preferment immediately incorporates acidity and organic acids into the dough, serving to reduce required floor time after mixing. As a result the baker can divide, shape, and bake in substantially less time than if he or she were using a straight dough.

- Rye flour offers some specific considerations. When baking bread that contains a high proportion of rye flour, it is necessary to acidify the rye (that is, use a portion of it in a sourdough phase) in order to stabilize its baking ability. Rye flour possesses a high level of enzymes compared to wheat flour, and when these are unregulated, they contribute to a gumminess in the crumb. The acidity present in sourdough reduces the activity of the enzymes, thereby promoting good crumb structure and superior flavor. “

Proofing

Proofing can refer to activating the yeast in warm water or allowing the dough to rise as we use it in home baking. Professional bakers use the term fermentation when it comes to allowing the dough to rise either shaped or unshaped. It’s a little less confusing that way.

Yeast dough requires time, temperature and humidity to rise. Between the initial rise of the dough to the final rise of the shaped dough, there can be 3, 4 or more. Professionals use proofers to manage these requirements. At the bakery, I had a proofing box, which held sheet pans of products. At the bottom of the proofer was a container to hold water. The temperature could be set as desired. This can be easily duplicated at home with an oven.

In the summer, I have no problem with yeast dough rising, even the rich ones. However, in the winter, my kitchen is cold and it can take an eternity to get the dough to rise. So, I make a proofer in my oven. Just place a 9x13 inch pan of hot water in the bottom of the oven about 10 minutes before you are ready for the dough to rise.

This can be the first time or after shaping and setting it to rise before baking. Put your bread in the oven and close the door. I generally remove the water after about 30 minutes. Just make sure the temperature stays between 80 and 90 degrees. You don’t want the dough to rise too rapidly or to over ferment. Remove the product before preheating the oven for baking.

A second way is to use the light in the oven. Simply turn the light on slightly before, or even when you put the product in the oven. No water is necessary. Close the door and monitor the temperature. If the oven gets too hot, prop the door open slightly to maintain the temperature.

Important Temperatures for Breads

Above 50 degrees to activate the yeast

90 to 100 degree water to proof yeast

80 to 90 degrees to proof the dough

139 degrees the yeast is killed

Cold water should be used if making dough in a processor as the speed of the blade is about 30 miles an hour. This heats the dough. If warm water is used, the dough can become overheated.

Lukewarm water or liquid can be used in breads made in a mixer to give them a start on rising.

Baking the Finished Product

Knowing a few things about the final process, will help give you the loaf you are looking for.

Make sure the oven is completely preheated before putting the bread in. If it is a lean bread, the temperature is usually fairly high. For sweet breads, the temperature is lower as the dough usually contains butter, sugar or honey and possibly milk or cream, making it ripe for burning at high temperatures. I double pan any sweet bread, or bread with a lot of butter, chocolate, honey, cornsyrup, etc. This slows the heat to the bottom of the bread so that, when finished, the bottom is about the same color as the top of the bread.

Creating Steam in your Oven - I don’t usually create steam in the oven when I bake sweet breads. But often do for lean breads where I want a crusty finish. The steam should only last about 8 minutes. Professional ovens have steam injectors so it is easy to give it several bursts of steam to obtain a crusty finish. There are several ways to create steam.

Water - A pan, such as a 9x13 inch pan, can be put in the bottom of the oven and filled with several cups of hot water.

Ice Cubes can be added to the pan instead of water. This has the advantage of not having to pull out a pan of really hot water from the oven after about 8 minutes.

Misting – Another method is to use a mister and spray the oven every 2 minutes for the first 8 minutes of baking. Some people spray the interior of the oven before putting the product in to bake. I don’t favor this one, as I once blew out the oven light which was a mess to clean up.

Slashing the Tops

Some breads require the tops to be slashed just before they go into the oven. It is important not to slash too deeply. About ½" is about as deep as the cut should go. This can be done with a single edge razor blade or a curved razor called a lame. Whatever you use, it has to be very sharp, so it doesn’t pull the bread but makes a clean cut.

Washes

Breads, lean or rich, often have some kind of wash applied just before going into the oven so the finished product will have a better finish or add to the crispness.

Water - Brushing the crust with water will add to the crispness of the baked crust. A mister is perfect here to give an even coat of water.

Whole Egg gives a shiny bronze finish. Make sure the egg is completely beaten.

Egg White Wash – Here again it is very important to beat the white well. This will give a transparent, very shiny finish.

Egg Yolk Wash – This gives a very deep brown finish with a soft crust. I like to use this on sweet breads.

Milk Wash – This gives a soft, not so shiny finish to the crust.

Cream added to egg yolk – Add about 1 tablespoon cream per egg yolk. This gives the deepest of mahogany brown finishes with a beautiful sheen. I use this on sweet breads.

Butter – Melted butter can be brushed on a loaf before going into or after removing from the oven. It will soften the crust with a dull finish.

Go here to see the different finishes.

Storing Baked Breads

Most baked breads freeze well. If frozen, they benefit from a few minutes in a 350 degree oven to return them to their original goodness.

Thaw the bread at room temperature. Place it in the oven. It is impossible to give times because there are so many types and sizes of bread. Larger loafs may take 20 minutes or so, smaller rolls 10 minutes. You only want to warm them not bake them so just feel them to see if they are warm or not.

Rosemary Mark says

Helen - fantastic detail in this post! As you know, I mainly bake with wild yeast water, but sometimes use dry yeast for speed or for rich doughs. Your explanation of the difference between active dry yeast and instant yeast is very helpful. I've had no trouble interchanging active dry and instant yeast, though mainly use active dry. I recall reading as you mentioned that the active dry is now formulated to be interchangeable, so I was glad you affirmed that. Thanks for this post, I'm ear-marking it and have shared with my niece.

Isabel Gardner says

You mention that to use frozen bread to put it in the oven at 350 degrees for a few minutes. Is that done while the bread is frozen? If not, do you defrost in on the counter or refrigerator? If there any guidelines about how long to leave the bread in the oven?

Helen S Fletcher says

H Isabel, I updated the instructions on storage. It is impossible to give times due the the any types of breads, densities, sizes, etc. The important thing is to warm them, not bake them again. The best test will be to feel them.

Belinda says

Very nice overview!! Bread baking can be quite overwhelming and it is very nice to have all this information in one place. Thank you!

hfletcher says

Thank you Belinda. I'm happy the article is of help.

Mary says

Thankyou Helen for this very informative article. I do bake my own bread but I think I learn something new with every loaf. Always learning! I make Sourdough mostly and that can be a bit hit and miss depending on the time of year - Hot or cold. But always edible!

I shall print this off to be able to refer to it easily. :))

hfletcher says

I'm with you Mary, always more to learn. I'm glad you found the article useful.

Sew Hoppy says

Fascinating reading; this is a keeper in my computer "bread box." I did the yeast test and was delighted it passed since it has been in the freezer for many years. Regarding refrigerating sweet dough before rolling out; how would this work for bread dough? Regarding yeast & flour, my usual bread dough has 26 oz AP flour and 2 1/2 t dried yeast. Should I double the yeast?

hfletcher says

Hi, if the recipe is working for you than to with it. These amounts are general guides but not absolutes. If you think you want the bread lighter, you can add yeast but I wouldn't double it. Up it by a quarter to start.

Tim Malm says

Wow! Thanks for your very informative essay. It's a comprehensive collection of so much technical information about yeast and breadmaking, yet is accessible and easy to understand. Thank you for sharing your passion for working with yeast breads.

hfletcher says

Hi Tim, I love baking bread. Not sure what it is that fascinates me so. One of these days I hope to do a bread book. With everyone making bread these days, I thought this would be a good time to bring this out again and update it. So happy you like it.

Pete says

Very informative. Thanks. Just thought I’d mention that ‘lame’ has no accent on the ‘e’ and is pronounced more like ‘lamb’ (rhymes with ‘ham’).

hfletcher says

Thanks Pete. I have corrected it and appreciate the help.

Charlene Prather says

Thanks for the lesson! I've been baking bread (mostly sourdough) for the past year and continue to learn. In your section on proofing, I believe there is a typo in the section about proofing in the oven - it says 80 - 190 and I suspect you mean 80 - 90.

hfletcher says

Hi Charlene, I love bread baking. And yes, 90 is correct. Thanks for pointing this out so I could fix it.

Mary Soucy says

What an incredible piece of work and an amazing amount of information! I have learned so much! Thank you for taking all the time you did to put this together. I have added this to my Helen Fletcher Bible!! It is getting thick. :)

hfletcher says

Thank you Mary. I hoped you would like it.